You have undoubtedly forged an immensely successful career. How did a young Hungarian student find himself at Oxford during the transformative 1980s? What obstacles did you surmount to arrive at this remarkable juncture?

This exciting question exposes a profound truth: while the world may perceive our current status and accomplishments, it seldom witnesses the tribulations endured en route. Absent from our meticulously crafted resumes are the scholarships, publications, job applications that met rejection, and unsuccessful entrance exams. To the casual observer, it might appear as if my path unfurled effortlessly, a steady march toward triumph. Yet, I also have weathered countless setbacks and repeatedly confronted disappointment. A scientific vocation mirrors, in many ways, the climax of the movie "Forrest Gump," where a feather dances through the air and its final landing place is uncertain. Whenever I think about my life, that feather always comes to mind — a symbol of chance, blown by the wind, poised to descend anywhere else.

Surely, it must certainly be more than just luck...

My successful career is due mainly to the calibre of my parents and the mentors I encountered. We must not forget that there are individuals in everyone's life who greatly influence where that feather falls. Nagykőrös High School provided an exceptional education, complemented by many inspiring teachers. Subsequently, at the esteemed Albert Szent-Györgyi Medical University in Szeged, Professors György Benedek and Mihály Bodosi offered invaluable guidance. Upon my arrival at Oxford, Sir Colin Blakemore became my supervisor, and I received tremendous support from him. I want to give back all of this to the next generation.

Was Oxford your initial noteworthy encounter, or did other opportunities precede it?

Hungary began to open up when I was a university student. Exceptional academic performances opened doors to international summer internships. Consequently, I had the opportunity to complete an anesthesiology internship in Helsinki and a pediatric surgery internship in Athens. Additionally, I was fortunate to immerse myself in the scholarly environment of Groningen, Netherlands, for three months. In 1988, through the Hungarian Academy of Sciences - Soros Fellowship program, I had the privilege of studying in Oxford, joining a select group of ten students from Hungary. This experience played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of my scientific career.

Did you consciously prepare for a scientific career even from a young age?

I studied diligently and, based on my exam results, was consistently among the top performers. However, my drive wasn't solely for achieving good grades; it stemmed from a genuine fascination with medical science. I enjoyed nearly all of my scientific subjects—it was more than just academic pursuits; it was a true passion.

Was it love at first sight with Oxford?

At first, I didn't quite understand why Oxford was considered such a prestigious university. The graduate program operated in a notably different manner compared to what I was accustomed to back home. At Oxford, they entrust students with the autonomy to make their own choices. No one dictated which research area to focus on, when to work, how long to stay, or how to pivot research directions. Nobody tells you which research area to focus on, when to come in to work, how long to stay, or how to change the direction of your research. That's the secret of Oxford—they give you the freedom to take the initiative and determine your path, driven by personal motivation.

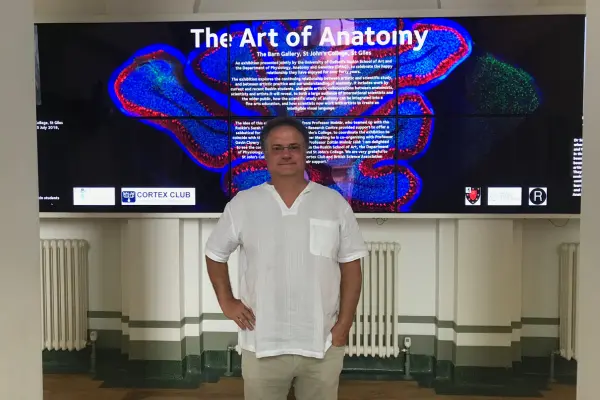

Oxford is a quaint town where students and professors cross paths wherever they go, making it feel like the campus is an integral part of one's day. Despite its small size, Oxford upholds an exceptional standard, serving as an immense source of motivation. While I deeply cherish the time I dedicate to neuroscience, I also have the opportunity to attend captivating lectures on subjects like history, literature, or psychology. We can immerse ourselves in exquisite art exhibitions or concerts within minutes of our apartments. Furthermore, the vibrant and international atmosphere adds an extra layer of enchantment. Yes, from the beginning, I was captivated by Oxford's irresistible charm.

At what point did you have the epiphany that the intricacies of the brain and the field of neuroscience are far more exciting than you initially anticipated during your student days?

I have always been interested in neuroscience, and to this day, I find it fascinating that I can explore such a complex system. Several defining moments led me down this path, which I still recall. As a young student, I regularly read articles in the magazine "Természet Világa" (World of Nature). I watched the scientific news program called "Delta," as well as live lectures by János Szentágothay about the brain on Hungarian television. It was during this time that I began to admire neuroscience. Later on, I was drawn to neurosurgery and the ability to diagnose and heal as a practicing clinical physician. However, this slowly changed when I received the scholarship.

When and why did you decide to choose research instead of pursuing a medical career?

Even after the scholarship and my completed PhD, I intended to stay in the field of neurosurgery. However, I was then awarded an additional three-year scholarship from the Medical Research Council, and even before concluding that, another scholarship followed at Merton College. It was an opportunity too great to turn down. I firmly believed that the knowledge acquired through research would profoundly enhance my clinical practice. As my success in research grew, fate intervened, I met my wife, Nadia, and it became clear that I would dedicate myself fully to research.

Neuroscience is a fascinating, rapidly evolving field, and you also have numerous commitments at the university. Do you manage to unwind or do you "take your work home"?

What greatly helps is the diverse nature of our work. Throughout the day, we must seamlessly transition between various roles, switching from researcher to instructor or administrator and becoming family members by the end of the day. I believe genuine success is rooted in one's ability to adapt swiftly to the ever-changing dynamics of the day.

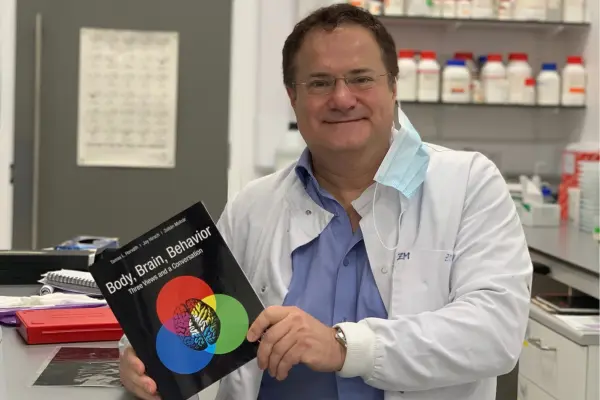

I deliver lectures and conduct practical sessions for 160-200 students in the mornings. Additionally, I facilitate small-group tutorials in my teaching room at St John's College twice a week in the afternoons. During these tutorials, I have the privilege of working closely with 2-3 exceptionally bright and diligent students. The subjects I teach encompass anatomy, histology, physiology, endocrinology, and pathology. I must prepare for these sessions as the students are required to submit an essay for my review, reflecting on the lecture and tutorial, which they mail me the day before. Although my work is diverse, striking a harmonious balance between my teaching responsibilities and pursuing research that can compete internationally proves increasingly demanding.

A pressing concern for the future is how we can ensure that medical students are guided by educators who remain actively immersed in research and can share the latest findings with them. However, it's not just about sharing the results but also the doubts. After all, certain aspects of our present teachings may not necessarily stand the test of time. It will be up to today's medical students to judge that. Critical thinking is crucial in this profession, as we need practising physicians capable of reshaping the future of medicine.

Do you have any free time? How do you like to spend it?

My life revolves around the university, so I frequently engage in official events and dinners, allowing me to meet many inspiring individuals, including doctors and representatives from various scientific fields. When truly unwinding, I find solace on the tennis court. I play tennis 3-4 times a week and am proud to be a member of four tennis clubs. Additionally, I have the esteemed role of Honorary Treasurer at the Oxford University Tennis Club. Collecting antique tennis rackets is one of my cherished hobbies, and I also find relaxation in taking walks and gardening.

The lectures on the history of neuroscience or the life of Thomas Willis within the framework of NeurotechEU are fascinating. Do you have a historian's vein as well?

I have a passion for history, particularly the history of scientific research. I find it fascinating to delve into the origins of certain concepts that continue to shape our research today and uncover the misconceptions held in past centuries. It raises the question of what changes and how our current understanding may be proven erroneous in a few years.

I became interested in Thomas Willis (1621-1675) when I began teaching second-year students who often struggled with neuroanatomical terminology. Latin or Greek names referring to the brain's shape, colour, patterns, or texture have been preserved over time. However, understanding them requires delving into history. Many of these terms are associated with Thomas Willis, who resided in Oxford, yet his life story remained largely unexplored. I had numerous conversations with Trevor Hughs in Oxford and Alastair Compston in Cambridge, both esteemed experts on Willis, and gradually I became well-versed in his work, too. We recorded these discussions, making them accessible to anyone interested. Additionally, I am honoured to be a member of the Oxford University Medical Educators' Club, known as the "Circle of Willis."

If you weren't a neuroscientist, what profession do you think you would enjoy?

I would have enjoyed being a clinical doctor. My brother, Béla, is an ENT specialist, and together with my brother Elek - also a neuroscientist – we sometimes envy him. It would have been wonderful to become an international athlete as well. I took tennis extremely seriously during my teenage years, regularly competing in local tournaments. However, my parents were afraid it would affect my studies. Thus, I had to put it on hold. I only re-committed at the age of 35.

I wanted to try myself as a sports reporter as well. Once, while attending a tennis match at the Queen's Club, I sought shelter from the rain under the awning. That's where I met John Inverdale, a BBC sports commentator. We talked, and I mentioned that I would aspire to be a sports reporter if I weren't a neuroscientist. I told him that I loved tennis so much that one of the exam questions for my second-year medical students would be about the brain areas activated in a tennis player when returning a serve. The following day, many people contacted me to tell me about John's recounting of our meeting with Peter Fleming on the BBC. Unfortunately, he mentioned the exam question as well. I had to change those urgently. There was a lot of amusement in the dean's office when I told them why! The moral of the story? I shall never again reveal my intentions to any BBC reporter.

After spending so many years abroad, how much have you changed? How do you manage to preserve your Hungarian identity?

Oxford is permeated by an academic, highly traditional atmosphere. Although foreigners can quickly integrate here, they can never truly become English. Yet, there is no necessity for that. Universities are progressively becoming more international. When I first arrived, I was the sole foreign university lecturer in our institute. Nowadays, half of the professors are. What matters lies solely in their research output, teaching methods, and professional expertise.

An international mindset permeates the atmosphere. The first thing one learns here is the multitude of behavioural norms and expectations. I like that there are many foreigners and the need to adapt one's interactions with each person individually. Upholding the unity of an international group is a great challenge, as well as making the students understand that they need not compete but rather collaborate, for we are all in the same boat. The cost of medical training in Oxford is half a million pounds, funded by taxpayers. We bear a substantial responsibility to select students who are not only exceptionally talented and resilient but will also go along this path successfully. They should be exceptional during the six years at the university and in the following 40 years, as they operate as partners.

My wife is from Lausanne, from an Italian family, hence our shared enjoyment of fine cuisine. I love Hungarian dishes and usually cook goulash or stew for our guests, which is always a big hit. Coming back home, I love experiencing the atmosphere of traditional Hungarian taverns, and I had an incredibly delicious lunch at Kaparó Csárda on my way to Debrecen. I appreciate their dedication to preserving regional cuisine.

What advice would you give to students of the University of Debrecen? What should they do to achieve similar successes?

Firstly, be assured that you are in an ideal place. Recognize how lucky you are! Many seem to fail to grasp the exceptional quality of education they receive here. My second piece of advice is to not to be passive! Everyone decides for themselves what they want from life. If a subject captivates you, do not hesitate to immerse yourself further! Hungarian universities progressively embrace internationalization, affording opportunities to connect with international students, engage in conversations, and exchange experiences. Seize this opportunity as these connections can profoundly benefit your future, and these friendships can endure a lifetime. Today's generation has much more possibilities than we had back in the day. They can explore the world, learn languages - it's essential to enjoy the fact that the world has expanded!

What opportunities do you see within NeurotechEU?

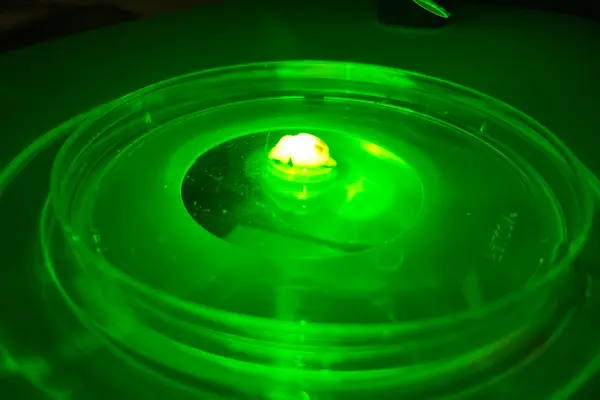

NeurotechEU offers a wide range of international education and research opportunities at all levels. The significance of digital technologies is steadily increasing in research, patient examination, and monitoring. NeurotechEU's partner universities are keen on exploring the potential benefits these technologies offer in healthcare and the tracking of patients beyond hospital settings.

Using smartphones or smartwatches equips us with a wealth of information that could be utilized in diverse ways, be it in the pharmacological treatment of neurodegenerative diseases or advancements in developmental studies. Examining the impact of environmental factors during pregnancy or early infancy holds substantial importance in understanding future conditions, albeit requiring decades of research to unveil precise causal connections. One such topic was recently addressed in a NeurotechEU webinar that I organized and is accessible online.

In the "Exciting Faces of NeurotechEU" interview series, whom would you prefer to read about, and what would you ask them?

I highly admire Professor Robert Harris from the Karolinska Institute. Not only does he play an active role in NeurotechEU, but his articulation of the project's potential challenges impressed me immensely.

Universities are interested in having the best professors and students and excelling in various subjects. However, university education still heavily relies on traditional lecturing methods, resembling those employed centuries ago, despite the availability of alternative possibilities.

NeurotechEU has the potential to revolutionize the education of future researchers who are accustomed to collaborating within international teams spanning multiple countries. Regardless of geographic location, the internet allows individuals to access research on global and international topics. Universities must keep pace with this trend and adapt. Professor Harris possesses remarkable insights in this regard. I am intrigued to learn his perspectives on how education will evolve in the next 50-100 years, as I firmly believe that significant transformations lie ahead.